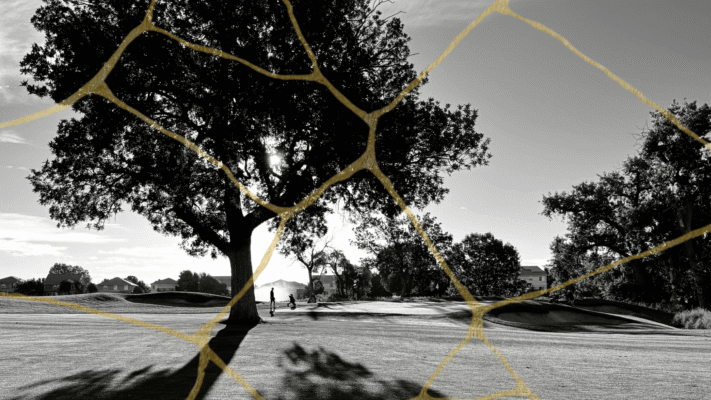

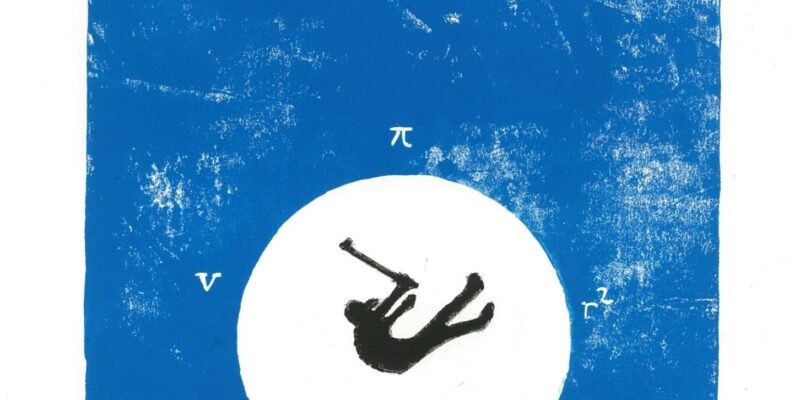

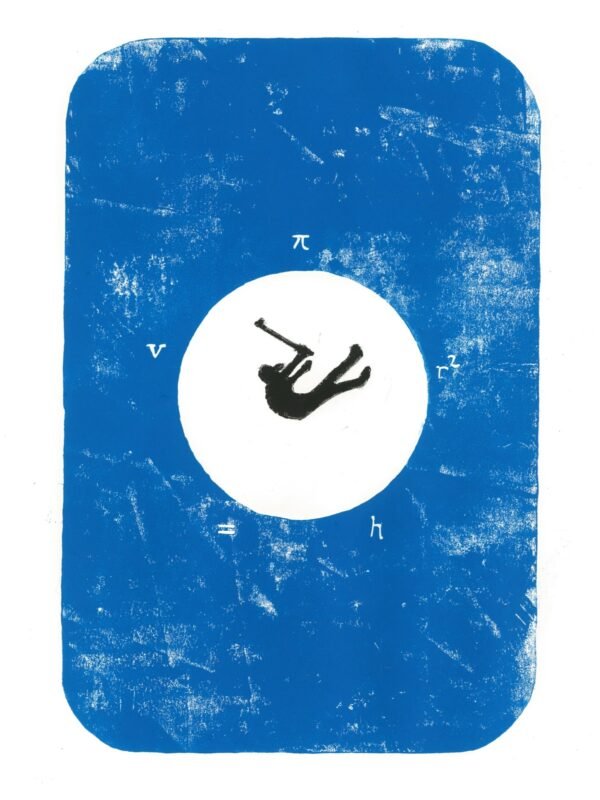

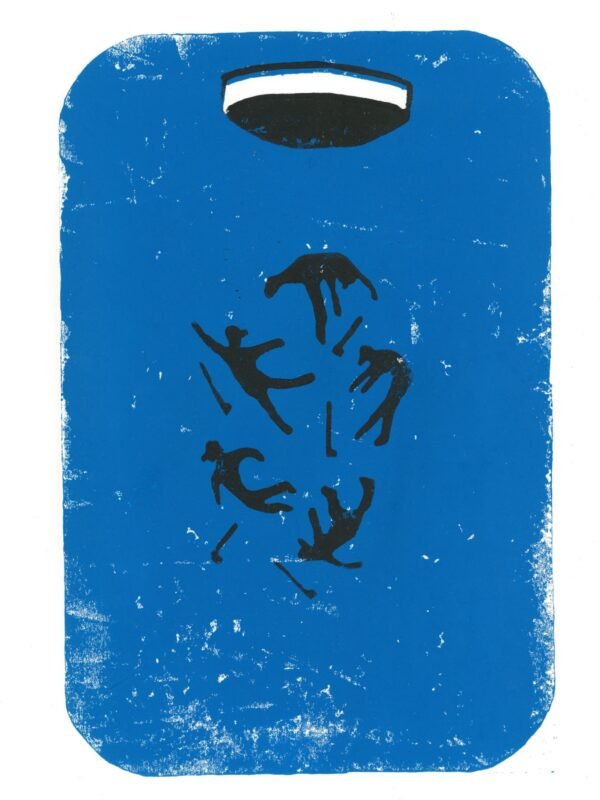

Matt Chominski’s essay ‘Holes: A Philosophy of Absence’ for our third issue might be the most intellectually stimulating read in the brief history of Depeche Golf. Matt’s writing was influenced by a number of sources: Blaise Pascal, Augustine of Hippo, Walker Percy, as well as the work of contemporary philosopher Suki Finn. What follows is an exchange between Matt and Suki on holes, golf, and golf holes. The corresponding artworks by Barry Bradshaw were originally created for the magazine piece.

MC: What is it about holes, absences, and other liminal phenomena that intrigues the philosopher? Can you explain how those of a certain type of philosophic persuasion approach these topics and why they think them worth the time, attention, and effort?

SF: Personally, what I (and others like Graham Priest) find intriguing is their contradictory or paradoxical nature. Whether they are existent or nonexistent, whether they are material or immaterial, whether they are absences of presence or presences of absence… And thinking beyond these binaries, about boundary cases or vague cases, for example, provides a clearer (and queerer!) picture of reality that has the power to disprove underlying assumptions in our very foundational understandings of logic, mathematics, metaphysics, and so on.

MC: How does the holes-interested philosopher motivate the average person to care about the questions the hole elicits? In other words, what’s at stake with the hole?

SF: I can tell you how philosopher and holes expert Achille Varzi did it – on US news, CNN! – by demonstrating that the fate of the United States (and all that it impacts) rested on how we count hole-punches in ballot papers when it came to voting in the elections. Such a simple practice in our political institutions requires us to think of the identity and individuation criteria for holes.

MC: When I look through a doughnut hole or into a golf hole, what am I looking at or through?

SF: Well, I suppose you are looking at, or through, what is between the edges of the lining of the hole. But if there is nothing for our vision to fix on, are we thereby looking at nothingness? With respect to physics, there isn’t truly no-thing wherever it is that we look, as there is always some-thing, at least, say, the structure of the Higgs field, or Dirac’s sea of electrons, in the vacuum state. There are no completely empty ‘gaps’ in the fabric of reality. So maybe there are no holes!

MC: Is the term “hole” mental short-hand—a linguistic crutch—used to describe something else or something about something else? Can I directly describe a hole?

SF: In a well-known article by David and Stephanie Lewis, the characters in the dialogue discuss whether the language of ‘holes’ can be paraphrased away using only instead the language of ‘perforations’. The motivation for attempting this alternative was to avoid referring, as you say, ‘directly’, to holes. That way, if it turned out that strictly speaking there were no such thing as holes, then we could more accurately speak of the shape of things which do exist as having a certain topology – as being perforated. But such paraphrase techniques are limited, at best.

MC: Does a golf ball fall into a hole or does it just fall into an absence where the golf course is not? Would you say the hole is there, at a particular spatial location, or is it just where something is not, negatively-understood?

SF: It depends on how you answer the previous questions, and if you think the hole is an actual part of the golf course, or if you think that the golf course is perforated! What the boundaries of the golf course are, what is to be included within it, will depend on whether you think the holes in the golf course are of the golf course. So – what makes a golf course, and what makes a hole?

MC: Does the subterranean situating of the golf hole grant it any uniquely particular qualities in the world of sport? Is it meaningfully different from a basketball hoop or croquet wicket?

SF: The golf hole has similarities and differences to other holes in sport, as you cite. With the basketball hoop, we can picture it as a very shallow ‘tube’ with an entrance and an exit for the ball to go through and come out of. The croquet wicket too, like the basketball hoop, outlines a ‘gap’ for a ball to move through. Whereas, the golf hole is more of a ‘dip’, which is a dead-end street from which the ball has to be retrieved from (though not necessarily in some forms of crazy golf where the ball goes into the hole and ends up sliding through some secret passage and ending up elsewhere!). The football goal net contains different sorts of holes – the net itself is ‘holey’, held up in rectangular goal-shape which itself presents, like the croquet wicket and basketball net, the outline to be aimed within, but more like the golf ball in the golf hole, the football does not end up out the other side of the goal. Unless the football net breaks, and the ball goes through the goal – but then how many holes would it go through? One, two, or more?!

MC: Does thinking about the hole offer any existential insight or enrichment? Does my life become more meaningful by thinking about the hole better?

SF: To think about holes is to think about complexities and nothingness, which is intimately connected to how we think of the every-day and everything. Indeed, many spiritual and scientific understandings of ‘how it all began’ is with nothing, including how we ourselves began our own lives as a sort of hole (a little cell that folds over on itself to form a tube that becomes our digestive plumbing system) which then come out of a hole…! There is no understanding of anything without an understanding of nothing.

Suki Finn’s recommendations for resources on these topics (including those mentioned in the dialogue above) include:

- Roberto Casati and Achille Varzi (1995) Holes and Other Superficialities, MIT Press.

- K. C. Cole (2001) The Hole In The Universe: How Scientists Peered over the Edge of Emptiness and Found Everything, Harcourt.

- Suki Finn (2018) ‘The Hole Truth’, Aeon, URL = http://aeon.co/ideas/Is-A-Hole-A-Real-Thing-Or-Just-A-Place-Where-Something-Isnt

- Suki Finn (2021) ‘On the Metaphysics of Nothing’, Philosophy Bites, URL = http://philosophybites.com/2021/03/suki-finn-on-the-metaphysics-of-nothing.html

- Suki Finn (2023) ‘The Metaphysics of Nothing’, The Internet Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, URL = http://iep.utm.edu/metaphysics-of-nothing/

- Suki Finn (2026) What’s in a doughnut hole? and other philosophical food for thought, Icon, URL = http://iconbooks.com/ib-title/whats-in-a-doughnut-hole/

- Markus Gabriel and Graham Priest (2022) Everything and Nothing, Polity Press.

- David Lewis and Stephanie Lewis (1970) ‘Holes’, Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 48.2, pp. 206-212.

- Jeanne Moos and Achille Varzi on Holes, CNN Live 2000 Florida Recount, URL = http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2nu-7asEy0U

Dr Suki Finn is a Lecturer in Philosophy and Gender Studies at Royal Holloway University of London. Her areas of research span feminist theory, bioethics, the philosophy of science, metaphysics, and logic. She is co-Director of the Society for Women in Philosophy UK.

Matt Chominski lives in the lovely West Chester, Pennsylvania with his wife and children. Most of his golf consists of chipping in the backyard while kids bound about a trampoline or hurl themselves through space on the swings. His degrees are in Philosophy, Political Science, and Philosophical Theology. He teaches Theology and Philosophy at Archmere Academy and writes a very occasional Substack titled “Fairway Philosophy.”

Barry Bradshaw grew up in the Garden of Ireland County Wicklow, surrounded by beautiful golf courses. He studied Audio Visual production at Arts University Bournemouth. Combining a need to create art and an obsession with the crazy game of golf, he may just have stumbled upon the perfect career! (Whatever that means).